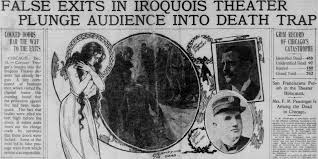

The Iroquois Theater Fire of 1903

- Notes From The Frontier

- Dec 3, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 13, 2022

It is the deadliest building fire in U.S. history but most people have never heard of it...605 dead and hundreds wounded in a matter of minutes, trapped in a magnificent brand new Chicago theater the promoters bragged was fireproof.

The beginning of the 20th century was a time of human innovation, invention, and ambition. It was also a time of human hubris—that arrogant belief that humans could challenge the gods and prevail. The Titanic was unsinkable. Wall Street was unstoppable. Natural resources were inexhaustible. Economic growth was illimitable. Zeppelins would revolutionize aviation. Machine guns would prevent wars.

So, when the magnificent, state-of-the-art Iroquois Theater in downtown Chicago was built in 1903, it was heralded as the world’s ultimate construction in theatre technology and aesthetics. Opulent beyond imagination, technologically stunning, it was the most expensive theatre construction in the world to date. Only ten years after Chicago had hosted the Columbia World’s Fair in 1893, Chicago was flaunting its prosperity and challenging New York as a theatre bastion.

Built in the heart of downtown Chicago on Randolph between State and Dearborn Streets, the six-story behemoth was billed as “Absolutely Fireproof” in its grand opening and advertising campaigns. The interior and foyer of the Iroquois Theatre were magnificent, with rich marble, pavonazzo pillars, ornately carved mahogany, soaring arches, and Rococo plaster dripping in ornamentation. The theatre had three immense seating tiers, plus numerous box seat chambers, and an audience capacity of 1,744, one of the largest theatres in the world at the time.

The Chicago Tribune wrote breathlessly of the opulent but innovative construction on November 4, 1903, several weeks before the theatre opening:

“The Iroquois is certainly unrivaled in perfection .... The enterprise which made the erection of the new theater possible has given the Chicago playgoers a virtual temple of beauty—a place where the noblest and highest in dramatic art could fittingly find a worthy home.... the theater is a place of rare and impressive dignity....” The press also heralded the many architectural and technical innovations, declaring the theatre “absolutely fireproof,” highlighting a special, asbestos, fire-proof stage curtain, and ample exists in all parts of the house.

“As for exits, they are far more numerous,” wrote The Inter Ocean newspaper on November 15, 1903, a week before the opening. “The entire north frontage [is] available in case of emergency. Another large emergency exit leads across the stage to Dearborn Street on the south side of the auditorium proper. The directness of entrance and availability of exits are a praiseworthy feature of this planned house.”

But an editor of Fireproof Magazine had toured the building during construction and was not impressed. The magazine noted "the absence of an intake, or stage draft shafts; the presence of wood trim on everything and the inadequate provision of exits." There were other problems as well. Although laws had been enacted 20 years before requiring doors to open outward, the Iroquois’s doors opened inward, this even when theatre fires had been an ongoing concern for many years.

The Chicago Fire Department captain, too, made an unofficial tour days before the official opening to witness the “absolutely fireproof” theater and noted that there were no alarms, sprinklers, telephones, or water connections. The captain mentioned the deficiencies to the Iroquois’s fire warden but he said they would simply be dismissed by the owners. The captain then reported his findings to his commanding officer, who was just as dismissive, saying nothing could be done so close to the grand opening.

The Iroquois opened on November 23, 1903 to over capacity crowds and was a ringing success. The opening attraction was Mr. Blue Beard, a spectacular burlesque with a dubious plot about a man who married women, then murdered them and hid their bodies in a closet. It featured famous vaudevillian Eddie Foy and included nearly 400 cast members, aerial ballet, and phantasmagoric scenes of castles, fairytale scenes, sparkling costumes, and elaborate set changes with filmy curtains. An audience favorite were the ballerina aerialists who floated over the patrons suspended from wires, showering them with flowers from huge baskets.

But nearly immediately, there were warning signs that the theatre was far from “absolutely fireproof.” During the first weeks in the Iroquois, the muslin curtains near the stage had caught fire several times. The staff had used Kilfyre canisters to douse the fires.

Five weeks into the Iroquois’s first performances, on December 30 after Christmas, the 3:00 matinee was the largest crowd yet, far beyond its 1,700 capacity, so that hundreds were admitted for the “standing room” areas at the back of the theater. Many of the estimated 2,200 patrons were children on holiday break with their mothers and sat on the floor filling the aisles and blocking the exits. No one could have dreamed that—in an hour—nearly a third of the audience would be dead.

Shortly after the beginning of the second act, at about 3:15 in the afternoon, a chorus of beautifully costumes women and men were singing a musical number, In the Pale Moonlight, in a dreamy, blue-lit scene when sparks from an arc light ignited the muslin curtain, probably from a short. Staff tried to put out the fire with Kilfyre cannisters, but the flames leapt up the curtain into the fly gallery where thousands of feet of painted canvas backdrops were hung. The staff tried to lower the asbestos curtain—later found to be made of wood pulp interspersed with flecks of asbestos which would have been useless—but the curtain snagged on a light reflector and trolley wires for the aerialists. The hanging backdrops and scene sets quickly burst into flames.

The immense crowd immediately panicked. The lead actor, Eddie Foy, ran out onto the stage and tried to calm the screaming masses. Later, he wrote that "It struck me as I looked out over the crowd that I had never before seen so many women and children in the audience. Even the gallery was full of mothers and children." It broke his heart.

But the hallways lead to locked doors. The three lower-level fire escapes into the alley were locked by a new kind of French locking system no one could figure out. The ventilation had been nailed shut. No sprinkler systems, no alarms, and the few doors that were forced open opened inward. Many patrons died piled ten high at the locked entrances.

Some of the performers fled out the back through a large, freight doors that, when opened served as a blast furnace for the fire. The burst of air caused the fire to explode in a massive fire ball over the audience.

Witness accounts said that aerialist Nelly Reed was still suspended in her harness in mid-air above the audience, unable to escape, when a fireball shot out from the stage and she caught on fire. She died of her wounds. Another aerialist named Florine also died.

Iron gates blocked the upper gallery from the lower level so that those with cheaper seats could not sneak down into premium seats. The largest death toll was in these stairways where hundreds of mothers and children were crushed, asphyxiated or burned to death.

Some patrons were able to reach fire escapes but the iron structures were unfinished and many fell to their deaths, although some later jumpers survived because the piles of bodies below cushioned their falls. One heart-breaking makeshift escape was fashioned by students of Northwestern University in a building next to the theater, who bridged the gap between the buildings with a ladder and boards and helped women and children cross on their hands and knees six stories above the street. The street below would come to be known as the Alley of Death in Chicago tours because the corridor was littered with bodies.

The Iroquois Theater fire is still the most deadly building fire in U.S. history and the deadliest theater fire in the world: 605 dead and hundreds injured. Although there had been numerous theater fires throughout the world, the Iroquois fire was finally the wake-up call for the world, perhaps because the majority of victims were children and women. It instigated massive reforms not only in theaters but in most buildings of public gathering. One innovation became standard: the panic bar on doors, first developed in England after the Victoria Hall disaster became required. Doors were also required to open outwardly and enforcement became much more strident across the country. Alarms, sprinkler systems, and emergency lighting also became more standard.

Interior damage was catastrophic throughout the theater, but the shell survived and was rebuilt and renamed the Colonial Theater. The venue was tarnished by such tragedy, however, and was demolished 20 years later. The Oriental Theater was built on the existing site. Last year, the theater was renamed the Nederlander Theatre.

Today, a bronze bas-relief plaque is permanently posted near the La Salle Street entrance of the Iroquois entrance. The Chicago Tribune described the marker depicting "the Motherhood of the World protecting the children of the universe, the body of a child borne on a litter by herculean male figures, with a bereaved mother bending over it.”

PHOTOS: (1) When the Iroquois Theatre in Chicago was completed in 1903 it was one of the premiere theatres in the world, reputed to have cost an unprecedented million dollars. Built in the heart of downtown Chicago on Randolph Street between State and Dearborn Streets, the six-story behemoth was billed as “Absolutely Fireproof” in its grand opening and advertising campaigns. (2) The interior and foyer of the Iroquois Theatre were magnificent, with marble columns, ornately carved mahogany and Rococo plaster dripping in ornamentation. The theatre had an audience capacity of 1,744, one of the largest theatres in the world at the time. (3, 4 & 5) The fire started on stage with the curtains and soon spread to the fly gallery above holding the canvas backdrops. A fire ball caused by opening freight doors in the back of the stage ignited audience members and the rest of the auditorium. Interior damage was catastrophic throughout the theater, but the shell survived and was rebuilt and renamed the Colonial Theater. The venue was tarnished by such tragedy, however, and was demolished 20 years later. (6) A crowd favorite were the ballerina aerialists who floated above the audience showering patrons with flowers. Two of the aerialists were killed in the fire. (7) A newspaper illustration of a makeshift escape over the “Alley of Death” created by Northwestern University students trying to save women and children six stories above the street. (8, 10 & 11) Piles of bodies were on the streets around the theater, and inside the theatre, piled ten high at locked entrances. (9) Bodies were piled inside ambulances and taken to morgues and funeral homes throughout the city. (10) Family members and friends came to the theater after the fire to try to identify their loves ones.

The Iroquois Theatre Fire was originally publishing October 14, 2019 on Facebook and NotesfromtheFrontier.com

149, 234 views / 1,338 likes / 68 shares / 281 photo views / 35 comments

© 2022 Notes from the Frontier